How fish move their fins- strategies to study and understand behaviour

How fish move their fins: strategies to study and understand behaviour

21.1.2026

Let’s imagine the following scenario. Children play on the grass, the terrain is slightly uneven, the sun is glaring. A child runs towards a ball and tries to catch it mid air. It sees, it runs, it stretches its arms and It grabs it.

During my PhD, I became increasingly interested in synergistic movement that gives rise to novel, complex and adaptive behaviours. Behavior is the complex and high-dimensional output of our nervous system, coordinated across various different bodyparts and integrating sensory (visual, proprioceptive, etc) inputs as well. How we run to catch a ball mid air is by no means a simple feat of the nervous system and given the dynamic nature of the movement hard to study. To this day, you cannot ask someone to run while their brain is being scanned and their behaviour monitored. We have to make do with inferring how the body coordinates limbs from observing their behaviour.

Since my laboratory (https://portugueslab.com) studied zebrafish (Danio rerio), I focused on how fish move their fins and coordinate them with the rest of their body (their tail and eyes). Larval Zebrafish have multiple advantages as a model system: they are small vertebrates and have evolutionary many linked structures to us [1], they are optically accessible for imaging and have a lot of genetic tools [2,3], there are many genotypes for ablation experiments, their motor system (especially the reticulospinal neurons i will come to later) is well studied [4] and they show a range of complex behaviors [5,6] which we wanted to use to study coordination.

💡Disclaimer: This work is part of my PhD thesis at the Technical University of Munich. You can also find the work at DNB and the preprint on Zenodo.

How to collect the data?

The first step was to collect the data of behavior. What even is behavior you might ask? Here, we define behavior as ’externally visible activity of an animal, in which a coordinated pattern of sensory, motor and associated neural activity responds to changing external or internal conditions’[7].

When capturing behavior in animal experiments, one normally follows these steps: acquisition, annotation, segmentation and classification. To understand the behavior you want to capture is the first step at designing the experiment and decide which data to capture. When dealing with behaviour we often have visual data (videos), but one could also track position via wearable trackers or another modality.

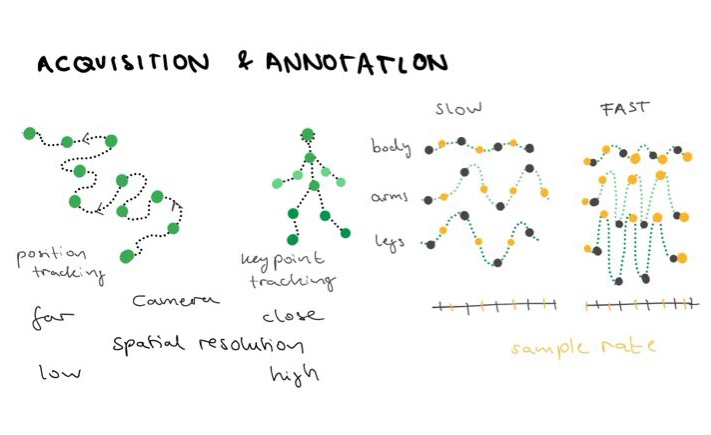

The Acquisition step depends on your animal and which type of data you deem relevant for your question, e.g. position data is fine for the migration study of birds but not sufficient when looking at inter limb coordination for which you need the specific positions of bodyparts in time (higher spatial resolution of data)(Figure 1). What your datas time dimension looks like also depends on your question. Behavior can be sampled at different time steps (sample rate), e.g. catching a dog walking can use a slower sample rate than a dog running after a ball. Figure 1 shows that on the right, when you have only the grey sample points they can describe the data (e.g. time series of a limb) relatively well for slow movements. For faster behavior you need a better temporal resolution to actually estimate, here we gain better resolution by adding the yellow points and doubling our sample rate (Figure 1).

The range of the behavior you capture also informs how you can capture it. If your behavior of interest is only the moment of an arm, the rest of the body can be restricted from movement for reproducibility. However, when you want to study how someone catches a ball mid air, the rest of the body is included in the motion. For our fish experiment, we want a high spatial and temporal resolution as fish move their tails at 20-100 Hz [8] and the pectoral fins are small limbs at the side of the fishes body (see more in Section 2.1. of the Thesis). The fish should also be freely swimming, therefore we aquired data using a camera setup on a motor gantry that follows the fish while it swims from above.

Figure 1: Data Acquisition and annotation.

The first data that we acquire is a high resolution video at a high frame rate (200 Hz), but what we essentially want to know is where each body part is at each time step. What we call the final data, is essentially the time series of the movements of the bodyparts. We do get these by annotating relevant features along the body of the animal (Figure 1 and Figure 2). This can be done by using either manual labour (subject to the bias of the experimenter and time consuming) or using marker less, deep-learning based annotation algorithms such as DeepLabCut [9] or YOLO [10].

The decrease in cloud computing necessary for the data processing means that many of these algorithms can be run in real time (although that often means 30Hz). A bias we have to think about when animals move is that we usually capture a certain camera angle which can cause distortions, occlusions or entirely miss other dimensions of movement. For studying coordination we ideally want to know the posture of the animal in 3D. This can be achieved by adding additional cameras for a stereo view and reconstructing the position from 2 views (this needs a calibration step from the cameras) and many out of the box algorithms such as 3D DeelLabCut already support this [9].

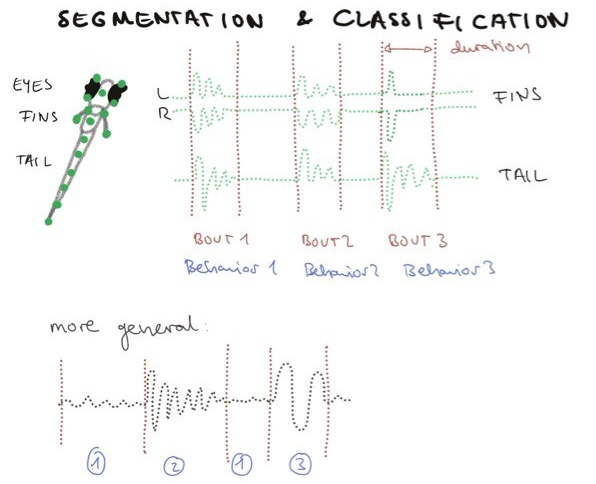

Segmentation deals with the question: How do we figure out when one behavior ends and the other begins? For this we can go one of two routes. Route one relies on you having prior knowledge on what the behavior you want to capture looks like, e.g. whether a horse walks, trots or gallops. Then the behavior can be classified in the video segments and the boundaries are set between (Figure 2) to inform e.g. how long the animal is performing a certain behaviour.

Figure 2: Data Segmentation and Classification.

This however relies on your understanding of behavior and on which timescale you would like to study it, which poses some challenges to naturalistic behaviors as we are not robots. Some of these challenges are that behaviour can evolve at multiple different timescales at the same time [11]. A mouse can be foraging for food on a large timescale (hour), their moment to moment behavior could be either sniffing (minutes) or walking (minutes) or eating (minutes) and the mouse can show second to second variability in behavior if e.g. it adapts to a new smell (Figure 3). Behaviors can also be combined, e.g. a mouse can sniff and walk at the same time .No behavior always looks the same and smaller classes of behavior could be attributed to variability depending on the timescale. All these aspects make a clear cut behavioural categorisation difficult.

Therefore Route Two uses data driven approaches such as unsupervised clustering to develop its own categories based on the data. This has the advantage that novel behaviours can be detected first and then named after by the experimenter. These approaches include density clustering of features of behavioral time series [12], HMM [13] or lexical approaches [14] that treat movements similar to language syllables stacked together in a sentence for generating a meaningful output.

In the case of zebrafish, segmentation is relatively straightforward as they swim in episodes called ‘bouts’ (Figure 2). Different labs have also clustered the behavioral repertoire of eyes [15] and tails [12], with the 13 tail categories by Marques et al being one of the most prominent examples of how fish swim in which context (spontaneous, hunting etc). Previous behavior classifications are a great starting point to also look at the data we got as well.

How do Zebrafish move their fins?

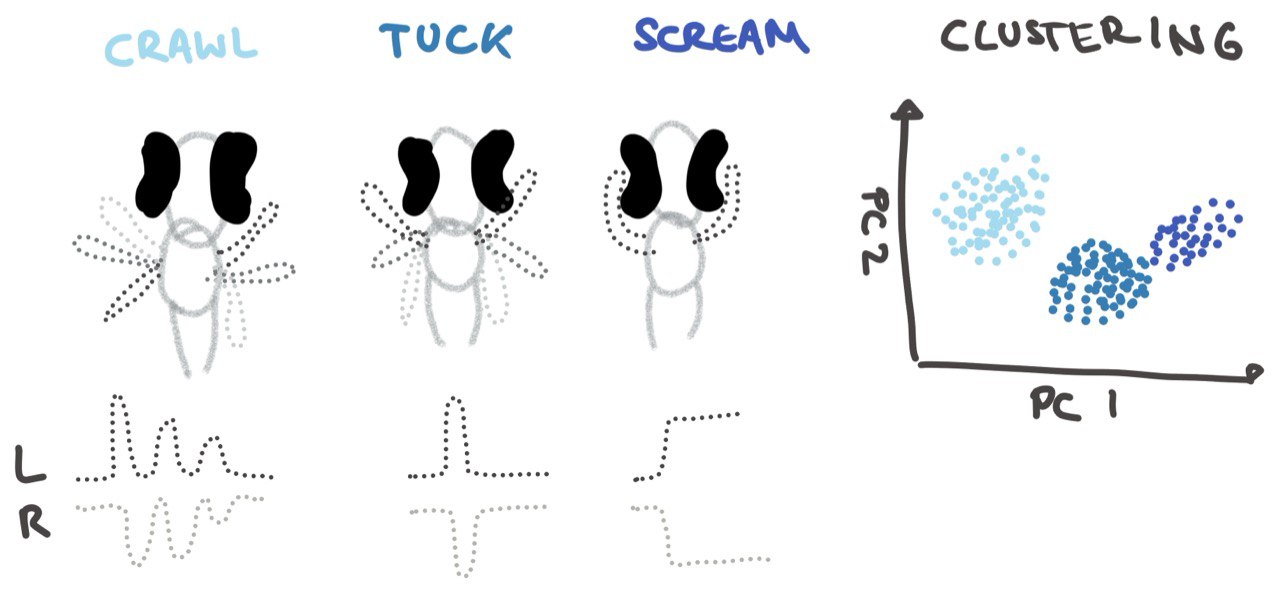

Zebrafish oscillate their tail as well as their fins. Previous research has proposed a set of categories for fin movements such as ‘Crawl’, ‘Tuck’ and ‘Scream’ [16] which is used for different speeds of movement (Figure 4). Crawl is used for slow swims, tuck for fast swims and scream is rarely seen in struggles. In our study we did try some of the classical approaches such as clustering based on the time series themselves and extracted features, which did not yield 3 categories as presented in Figure 4 but rather a continuum of varying fin movements (Figure 5). We saw fin movements vary along multiple different dimensions such as the number of oscillations and the amplitude of the oscillation peaks. The beat frequency, fin beat duration as well as the correlation between the fins in time. The previous clear cut categorisation is therefore seems too simplistic to describe fin behaviour.

Figure 4: Fin Movement.

How are fins and tail coordinated?

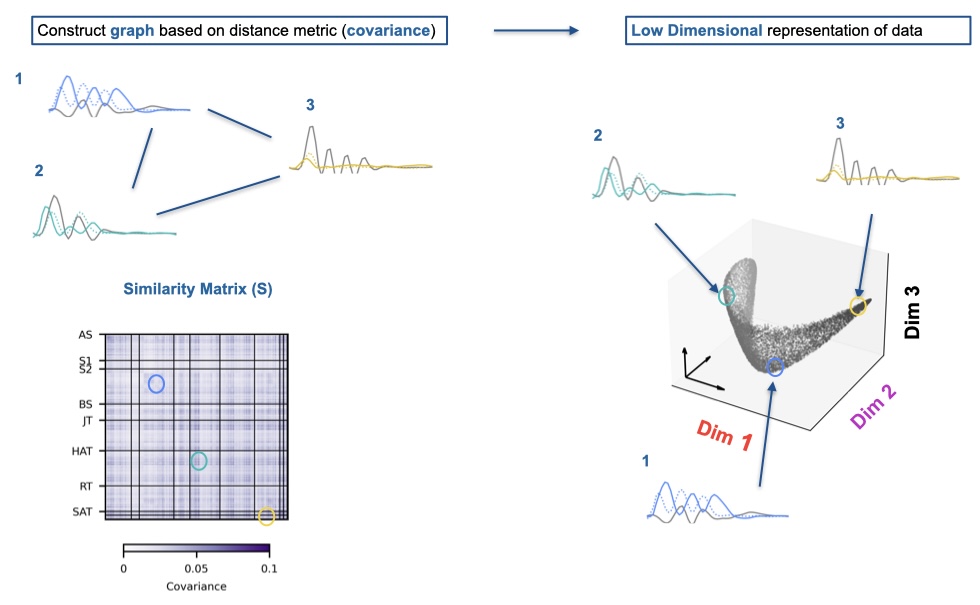

We figured there must be a better way to describe fin movements than clustering. To find out if there was any structure in fin movements, we explored the co-variance between the bout features by placing them in a low dimensional space using Laplacian Embedding based on a similarity matrix with covariance as a measure (Figure 5). We found that the low dimensional manifold was varying along 3 axes mainly, which were defined of features of amplitude, frequency and a nonlinear time vigour relationship akin to gaits. This embedding also partially separated bouts based on tail categories, which could inform whether some behaviors of fin and tail are stereotyped in their coupling. Stereotyped coupling is more efficient as both the fins and the tail will react fast to an input signal. A reason why the coupling between fins and tail might not be stereotyped is that fins likely react to vestibular, proprioceptive and mechanosensory inputs such as limbs in other animals [17,18]. This would cause more variation in the fin movements we observe. If there is coupling, it makes sense that there should be a neuronal link.

Figure 5: Fin Embedding.

But how is this implemented on a neuronal level you might ask?

The architecture and cell types involved in the generation of movement are well studied and highly conserved across species [19, 20]. I will give a brief overview of how the intention to move in the brain is translated into coordinated movements in vertebrates before moving specifically to what is known for fins and tail. The nervous system of vertebrates consists of the central nervous system CNS (formally known as brain) and peripheral nervous system PNS (all the other nerves in your body including your spinal cord), which activates your skeletal muscles to move.

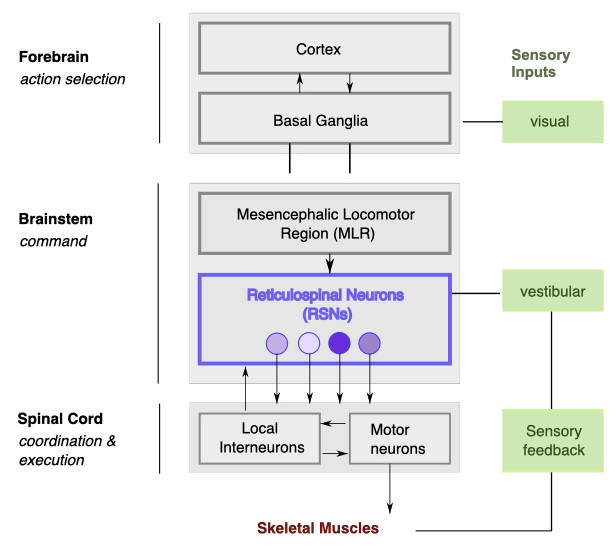

All parts of the nervous system partake in different parts of the process (Figure 6). After an external or internal impulse to move occurs. The action is selected in the forebrain (Cortex), and then mediated via the Basal ganglia to the Mesencephalic Locomotor Region (MLR) in the brain stem. The MLR recruits Reticulospinal Neurons (RSN), which send descending projections to local interneurons in the spinal cord, which drive motor neurons that activate the muscles in the body and limbs to move.

These interneurons in the spinal cord are part of networks called Central pattern generators (CPGs). Each limb e.g. the legs has a local CPG circuit in its corresponding spinal segment. These CPGs are networks of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons that can generate rhythmic output even without sensory input or brain signals. These CPGs give motor commands to the muscles. Commissural interneurons couple the left and right CPGs to generate alternating movements such as walking. Long propriospinal interneurons connect limbs with other body CPGs. These connections coordinate the gaits like Trot, Pace and Gallop. The reticulospinal inputs from the brainstem modulate which gait emerges by shifting the balance of excitation/inhibition across these interneuron pathways. Sensory feedback also plays a big role in coordination of limbs. This feedback can come in the form of Proprioceptive feedback or Vestibular inputs. For example: If a limb encounters unexpected resistance, sensory afferents adjust the timing of the CPG output to maintain balance.

Figure 6: Neural Control of Movement. Figure adapted from [20].

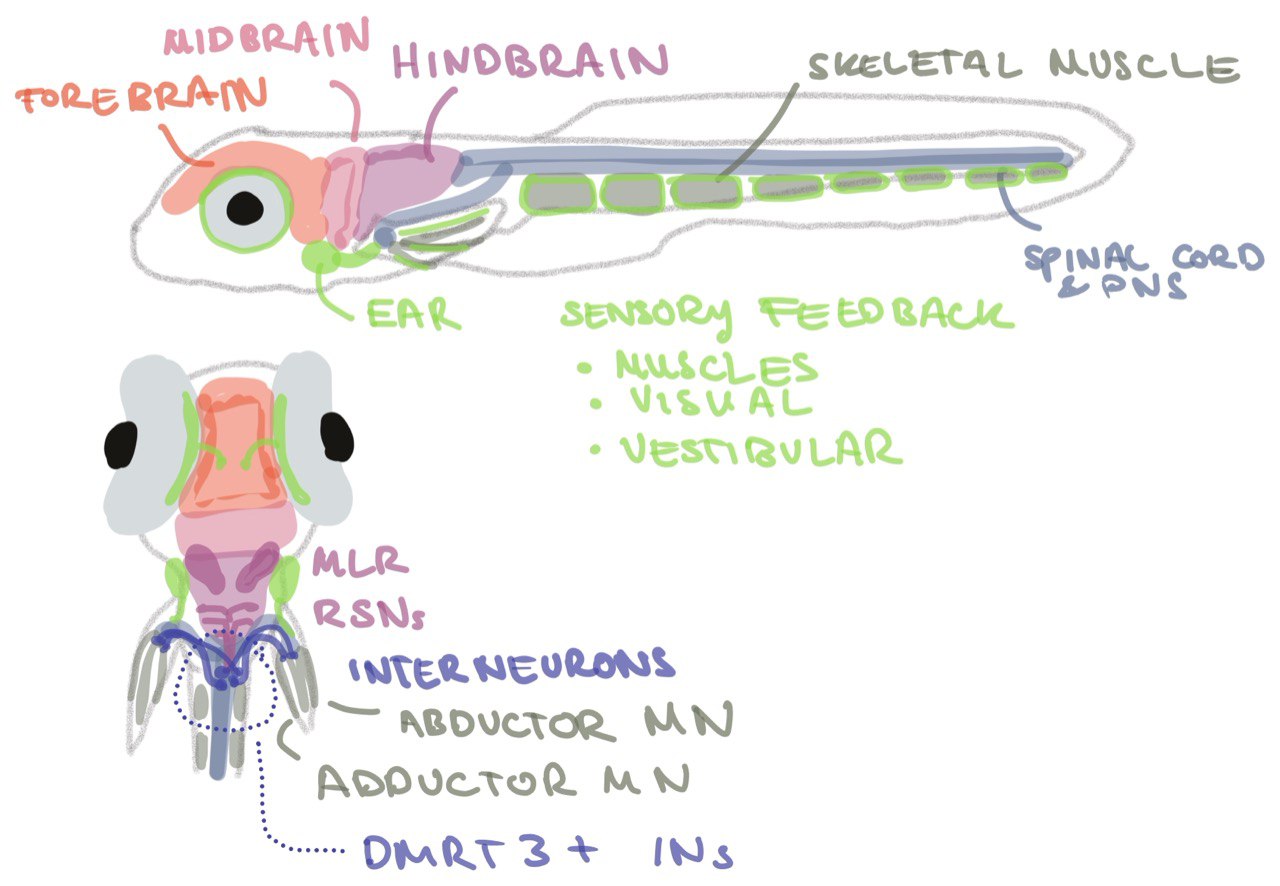

In Figure 7, I annotated the motor control generating brain areas in a zebrafish for better visualisation. This is highly simplified and the background literature on different neuronal subtypes contributing and influencing the variables of movement is large (see Thesis Chapter 1.3). We can think of the fins and tail both having their own local bodypart CPG, which are controlled in a synergistic /coupled or decoupled fashion to create coordinated movements of fins and tail. The neural link between the coupling is so far unknown. First experiments traced back neurons innervating the fin to the spinal cord where they make a connection with dmrt3 interneurons, potentially part of the fin CPG [21] (Figure 7). Their upstream targets are yet to be identified, but prominent candidates are V2a neurons as subsets of V0v and dI6 (dmrt3a) neurons receive input from V2a neurons directly, and ablation of these neurons altered left-right coordination in mice [22]. dmrt3 neurons also receive inputs from the vestibular system via CSF-cNs projecting neurons in the occipital/pectoral (Oc/Pec) motor column in larval zebrafish [18]. Posture is also affected by ablation of ontogelin [17], all pointing towards fin involvement in posture and the reaction to dynamic water conditions.

From the data we have, we can only infer what the neurons are likely doing. To fully understand the system we would need to do functional perturbations of the system that change the output of the limb CPGs, their interaction in a visible way for us to detect in their behavior. An alternative is to image the neurons in the brain and spinal cord, while the fish is swimmings as presented in novel microscope setups [23].

Figure 7: Motor control network in the larval zebrafish.

Why does this matter for us?

The automated analysis of zebrafish locomotion has evolved from labor-intensive manual tracking to sophisticated pose estimation pipelines that can extract subtle behavioral features in real-time. Tools like DeepLabCut and YOLO have made tracking and annotation cheap and accessible. Still the field faces a fundamental challenge of how to transform vast streams of coordinate data into biological understanding. Developing standardised behavioral ontologies as a lexical description of behavior will lead to meaningful comparison across laboratories. More open-source pipelines and hardware will enable smaller labs to contribute meaningfully.

For probing the circuit, real-time analysis coupled with closed loop optogenetic manipulation will enable live probing of the motor circuit while the fish is swimming. How is a pinnacle of engineering, in a microscope that is able to track freely swimming fish while imaging its whole brain [23]. This will truly open our understanding of how the brain generates coordinated movements.

Perhaps the most critical development is that we use methods that respect the continuous, hierarchical nature of behavior rather than forcing it into discrete categories. The tools and algorithms developed in the recent years are not all fish specific.

Let’s look beyond fish. Looking at the coordination of fins and tail, can tell us more about the function and development of our motor circuits. Fish were some of the first animals to develop the rudimentary architecture we now use to move and understanding how our brain translates thought into movement can not only inform the study for diseases affecting movement, such as Parkinsons and Huntington’s. It can also help inform our design decisions for making more naturalistic adaptable prosthetics in the future, which integrate brain feedback for movement coordination. Coordinated movement is often taken for granted in our daily life, but one notices how essential it is when it’s restricted temporarily or lost. I therefore hope my next project to be one that focuses on understanding brain signals and restoring movement ability in the emerging field of neuroprosthetics.

Every improvement in how we measure and analyse movement brings us closer to understanding a fundamental question I asked myself in the beginning of my PhD: how do neural circuits transform sensory input into adaptive behavior?

We’re not just tracking fish behaviour better, we’re decoding the computational principles that allow a cubic millimetre of neural tissue to navigate a complex, dynamic world.

References

[1] Babin et al. (2014). “Zebrafish models of human motor neuron diseases: Advantages and limitations”. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.03.001

[2] McLean et al. (2008). “Using imaging and genetics in zebrafish to study developing spinal circuits in vivo”. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20617

[3] Fetcho (2007). “The utility of zebrafish for studies of the comparative biology of motor systems”. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21127

[4] Metcalfe et al. (1985). “Anatomy of the posterior lateral line system in young larvae of the zebrafish”. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330307

[5] Bollmann (2019). “The Zebrafish Visual System: From Circuits to Behavior”. doi: 10.1146/annurev-vision-091718-014723

[6] Kalueff et al. (2012). “Zebrafish Protocols for Neurobehavioral Research”. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-597-8

[7] Eck et al. (1991). “Life, an Introduction to Biology”. 3rd ed. Harper Collins.

[8] Sánchez-Rodríguez et al. (2023). “Scaling the tail beat frequency and swimming speed in underwater undulatory swimming”. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41368-6

[9] DeepLabCut documentation: https://deeplabcut.github.io/DeepLabCut/README.html

[10] Ultralytics YOLO documentation: https://docs.ultralytics.com/tasks/pose/

[11] Datta et al. (2019). “Computational Neuroethology: A Call to Action”. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.09.038

[12] Marques et al. (2018). “Structure of the Zebrafish Locomotor Repertoire Revealed with Unsupervised Behavioral Clustering”. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.12.002

[13] Weinreb et al. (2024). “Keypoint MoSeq: parsing behavior by linking point tracking to pose dynamics”. doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02318-2

[14] Reddy et al. (2022). “A lexical approach for identifying behavioural action sequences”. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009672

[15] Dowell et al. (2024). “Kinematically distinct saccades are used in a context-dependent manner by larval zebrafish”. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.08.008

[16] Itoh et al. (2015). “Munch’s SCREAM: A spontaneous movement by zebrafish larvae featuring strong abduction of both pectoral fins often associated with a sudden bend”. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2014.12.004

[17] Ehrlich et al. (2019). “A primal role for the vestibular sense in the development of coordinated locomotion”. doi: 10.7554/eLife.45839

[18] Wu et al. (2021). “Spinal sensory neurons project onto the hindbrain to stabilize posture and enhance locomotor speed”. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.042

[19] Grillner et al. (2020). “Current Principles of Motor Control, with Special Reference to Vertebrate Locomotion”. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2019

[20] Arber et al. (2018). “Connecting neuronal circuits for movement”. doi: 10.1126/science.aat5994

[21] Uemura et al. (2020). “Neuronal Circuits That Control Rhythmic Pectoral Fin Movements in Zebrafish”. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1484-20.2020

[22] Crone et al. (2008). “Genetic Ablation of V2a Ipsilateral Interneurons Disrupts Left-Right Locomotor Coordination in Mammalian Spinal Cord”. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.009

[23] Kim et al. (2017) “Pan-neuronal calcium imaging with cellular resolution in freely swimming zebrafish”. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4429.url:https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.4429